Triple owners are passionate in the defense of their chosen mounts. They can't understand why every rider doesn't have one and every manufacturer doesn't make one. What's all the fuss about?

Despite the race success of MV and Triumphs, the four-stroke triple layout has never been the first choice of manufacturers for their production offerings. Only the reborn Triumph company flies the flag for threes today.

BSA/Triumph Tridents and Rocket 3s came to the party too late to stop the Japanese setting the multi standard with four pots. But when Yamaha decided to build a 750 four-stroke in the mid-Seventies it went for a three. And Laverda's triples were classics from day one.

A three pot motor is lighter and narrower than a four. At the same time it's smoother than a twin while retaining some of the stomp enjoyed by Bonnie, Commando and Yam XS650 owners. "You've got one too many pots on that, hur, hur," they tell triple owners. Mis-guided fools.

We ride a 1976 3CL Laverda, a '75 T160 Trident and a 1978 XS750 to see which is the best of the Seventies triples.

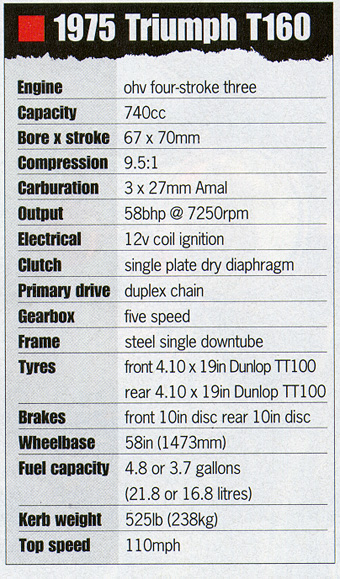

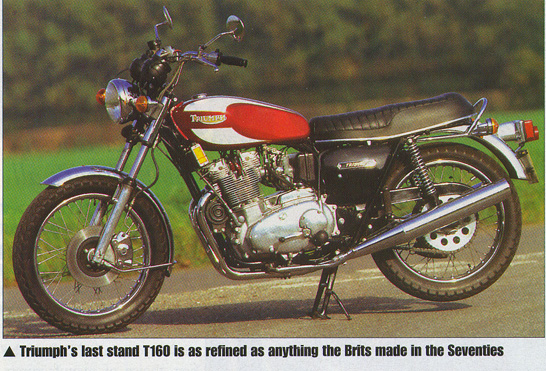

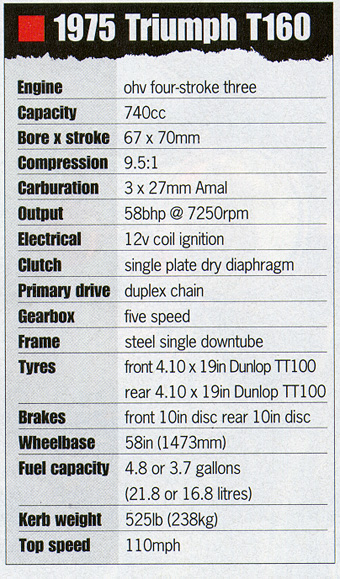

But Paul's words fall on deaf ears as I roar off into the sunset. The only way to make this three way triple test fair is to use standard bikes. So this 1975 T160 with only 5000 miles on the clock from new is the bike I want.

Looking at the condition of the rest of the machine I'm tempted to believe those 5000 miles are genuine. The Trident has a technical disadvantage compared to the Lav and Yam -- it has a pushrod motor where the other two use double overhead camshafts. And the Lav displaces close on a liter while the other two are 750s. The only deviations from standard on our test T160 are newly painted tank, a Boyer Bransden Microdigital electronic ignition system and a new saddle.

But the new seat hasn't bedded in to become favourite armchair comfy and after about an hour in the saddle all sensation has departed my backside. I decide to take a break to allow circulation to return and have a quick check round the bike. Apart from a slight weep at the head which later seals itself, all is well until I dip the oil tank.

Full when I left Paul's house, the T160's oil tank is 3/4pt of 25/50 down after 100 miles of motorway cruising. Is this the infamous oil burning that Tridents have such a reputation for?

|

Apparently not. With the oil tank replenished, consumption returns to normal for the rest of the test. These are two possible reasons for the triple's initially high thirst for oil. Paul changed the lube before I picked the bike up and thinks he forgot to refill the primary case which holds just over 1/2pt. The crankcase breathes into the primary to keep the oil level up with the excess returning to the sump. If the primary case was empty the oil tank would quickly lose 1/2pt. The other reason for the oil deficit could be sticking piston rings letting oil be sucked up into the combustion chamber. This can be caused by a long period of disuse, and when the rings free up from the pistons the problem is solved.

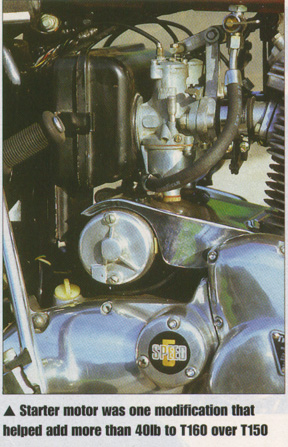

Paul had warned me that I'm unlikely to get much joy from the electric starter, because the temporary siting of the Boyer ignition box means he's had to fit a small battery. But ever the optimist I decide to give it a go on the cold morning of our test. With the three Amal Concentrics tickled -- the middle one by means of a quaint remote lever -- the Trident starts on the third push of the button.

Being used to the positive right side gear selector on my earlier T150 Trident, the T160's left shift feels alien at first. Where the slightest movement engages the next cog on the T150, the later machine's shift has a lot more travel thanks to the gearshift crossover Triumph fitted to the T160 to satisfy American laws. But I never miss a gear.

At 5000rpm some tingles start to come through the footrests, but rather than being unpleasant, these vibes are a reminder the the T160 is a performance machine with a few rough edges -- character as we call it. The very last T160's rider rests are rubber mounted.

Owners of dozens of triples, Paul and Andy always replace the rubber handlebar bushes on their bikes with solid items, so the only protection from vibes at the tiller are cushioned grips. The metal bushes are a good idea because they positively locate the bars. With wide export bars and rubber bushes a gyroscopic effect can be noted at the bar ends on uneven roads. And the Trident isn't vibratory enough to be uncomfortable in the absence of such niceties.

|

Under hard acceleration the Trident can be prone to shimmy. I've never ridden a Trident that didn't sometimes twich its rear. The reason is that the forks top out, making the front end light. The T160 has shorter forks with less travel than the T150, but the problem persists. Original hard Girling shocks fail to help keep things in line.

Under anything more than moderate braking the Trident nods its head like a fetlock tugging servant. The original fork seals are perished and most of the oil has disappeared taking the damping with it.

Triumph drew inspiration from its production racers when designing the T160, lifting the lower frame rails to improve ground clearance. The swingarm was shortened and the fork angle changed to retain the same wheelbase as the T150 and steering is sharp, even on 20 year old TT100s, but the footpegs and centerstand tang are easy to ground out.

Our T160 is keen to rev, despite its restrictive airbox and black cap silencers. With low gearing the Trident gets there quickly but runs out of steam at the top end. The factory only supplied bikes with 50 tooth rear sprockets. There were plans to offer 45 tooth alternatives to give higher gearing, but production ended before this happened. As far as top gear goes, 70mph is a shade under 5000rpm, which makes for comfortable cruising.

"The racers were excellent on long circuits where they could exploit their power to the full, but extra weight could put them at a disadvantage against twins on short circuits," says Hele.

"Compared to twins of the same capacity, triples can rev higher because of their smaller pistons and valves. It's easier to extract power from a four but a three has the advantage of being smaller and lighter," Hele adds, pointing to the racing successes of BSA/Triumph triples and the illustrious MVs.

Grand Prix racing provides a good example of the benefits of triples over an ultra smooth four. "With their smooth power delivery fours can slip on corners. They lack the punch of a three. Some manufacturers even built GP two-strokes that fire irregularly to improve grip on corners," says Hele.

Triumph experimented with the 180 degree layout Laverda favoured for its early triple, but results weren't satisfactory. "Up to about 4000rpm the bike felt like it was misfiring," remembers Hele. "The only advantage of the 180 crank is lower manufacturing costs. We settled on the 120 degree configuration because it was so even. And that sound!"

The reborn Triumph company in Hinckley, Leics is enjoying huge success with triples. Since the first Hinckley bike rolled off the line in 1991 over 45,000 threes and fours have been sold.

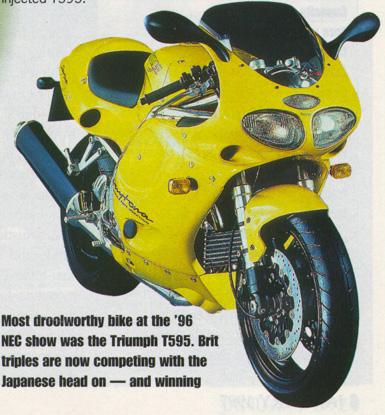

At the moment the press and the buying public are being wowed by the new 955cc T595 Daytona, the first true British sports bike for decades. With nearly 130bhp on tap and a sophisticated electronic management system that delivers three million instructions a second, the mighty three is showing the Japanese a thing or two.

Already Triumph has more than 1000 orders for the T595 Daytona, occupying production capacity until the end of this Spring. Last year Honda sold less than 2000 of its FireBlade superbikes in the UK, making Triumph's achievements with a bike that no member of the public has ridden yet all the more impressive.

Triumph is unique in today's market in offering four-stroke triples. I ask Hinckley's engineering manager Stephen Steward why the company opted for this particular engine configuration.

"In building a triple we were able to offer something different from the competition's across the frame fours while building on a Triumph tradition. It's easier to extract more power from a four," concurs Steward, "but we haven't done bad with the fuel injected T595."

|

Most droolworthy bike at the '96 NEC show was the Triumph T595. Brit triples are now competing with the Japanese head on -- and winning |

|

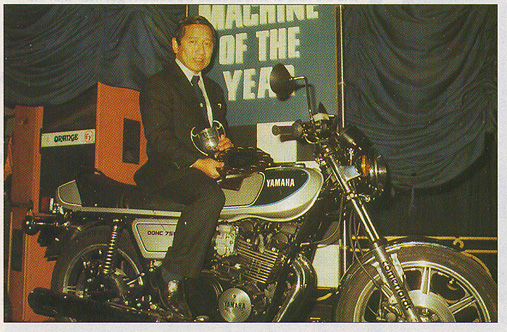

Mitsui boss Ishizakasan picks up Motorcycle's Machine of the Year award for 1977 |

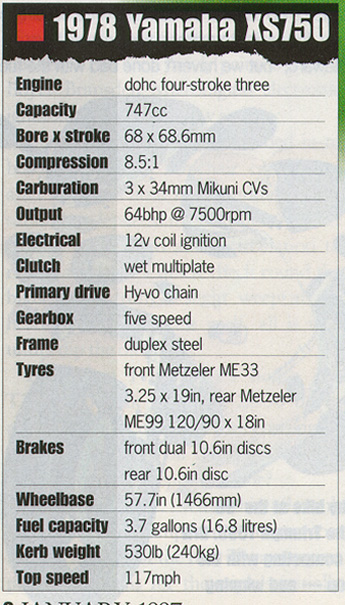

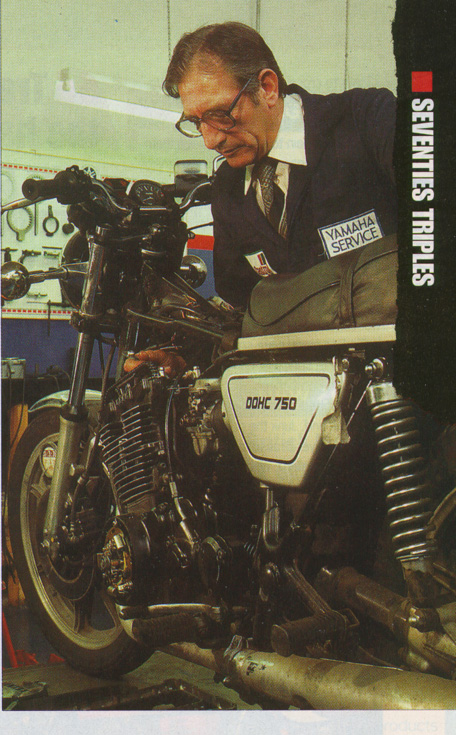

Yamaha's XS750 has a tenuous claim on the classic tag. Buyers of the bike when new believed they were signing up for Trident race performance, Japanese reliability and BMW shaft drive quality. The XS' engine layout is unusual for a Jap four-stroke and it topped MotorCycle's readers' poll machine of the year in 1977.

But ultimately the XS -- the only production Japanese four-stroke triple -- is a typically inscrutable Seventies Oriental bike. The main reminder that I'm not riding something like a Honda 750/4 is a torquier motor giving plenty of stomp out of the bends.

White finger tingles I remember from experience of Seventies Jap fours threaten to appear. The Lav and the Trident have their own resonant frequencies but the high revving Yam has tingles on another level. No wonder modern manufacturers put balance weights in the bars of their multi-pot offerings. Hollow folding footpegs mean that the vibes don't reach my feet.

|

But I'm ready to be impressed by Mick Worsdall's 1978 example of the Jap three. Rave press reviews served the bike well and, despite the bike being launched in Morocco, the reports don't appear to be drug fuelled frenzies one would imagine or even hope for.

A whistle, a squeak, some camchain tinkle and Mick Worsdall's Yam starts first time. The Yam revs out as cleanly as a four in keeping with its 9000rpm red line. Appearences are deceptive and the XS feels slowest of our three pack but the speedo says this triple is on the pace. A relaxed five grand in top is 70mph. And three discs that actually work gives the Yam braking advantage over our other test bikes.

Torque reaction is not as extreme as on a BMW. But the power sapping drive still makes its presence felt when throttling back on straights if not on bends. The corpulent lines of the XS suggest excess weight but on the move it sheds its load as easily as the Trident except during low speed manouevres. If only the same could be said of the Laverda.

Ground clearance is minimal even compared to the Trident. But folding footpegs are forgiving enough and won't throw the rider off. Neutral handling makes for an easy ride. Handlebars aren't as high and wide as the Trident and not as narrow and low as the Lav. The XS definitely lives up to its sports touring designation.

A Koito halogen headlight promises to be much better than the Triumph's, and switchgear and clocks are high quality. Indicators are self cancelling.

Mick paid a paltry £100 for his Yam and spent the winter of 1989 restoring it. Spares availability is good but parts can be pricey. He fitted a new original exhaust system and rebuilt the standard shocks. Two-pack paint was applied by Mick to stunning effect. Show awards suggest fellow enthusiasts approve.

"For my money the XS750 has as much character as any Seventies Jap bike," says the Norfolk man.

| |

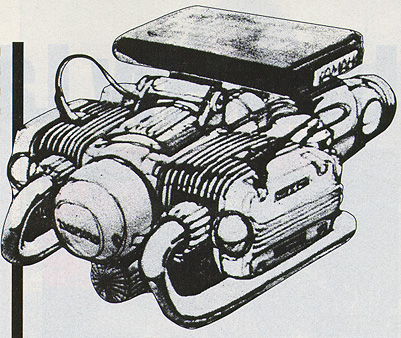

| Japanese translation of BMW boxer lacks originality. Yamaha retained shaft drive design for XS750. | |

Before producing the XS shaft drive triple, Yamaha looked at a variety of engine layouts. A flat twin was considered but rejected for looking like a BMW engine. The same fate befell a Guzzi like vee-twin. Also Yamaha wanted to avoid the slow, clunky gearchange and torque reaction of longitudinal cranks. Honda and Kawasaki were then producing fours and Suzuki was soon to join them, so to be unique Yamaha had to have a three.

Yamaha's three met the company's criteria for a sports tourer and gave the world something slightly less bland then the run of the mill Universal Japanese Machine.

|

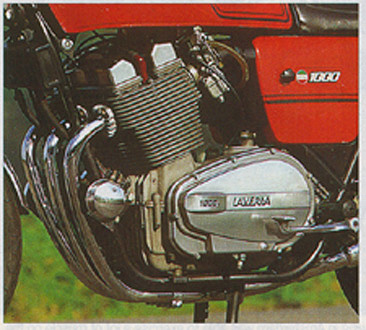

| Chunky motor looks as solid as it is. You won't have much trouble down below, guv. |

To start the 3CL from cold, first find the triple's cunningly concealed choke lever. Experience of Jotas has mad me wise to the ways of the Breganze boffins -- the lever is mounted down by the oil cooler. Half choke and a couple of stabs on the button has the Bosch starter motor doing its stuff.

Laverda's one litre brute doesn't politely request rider input -- it makes demands. Wrestling the top heavy beast through yet another bend, I wonder if the Lav's musclebike title has more to do with an ability to pump up the upper body than the machine's raw power.

But haul it down into bends to counter understeer and taming the Lav is a sensual physical experience. And the 3CL has the most ground clearance of the three bikes on test here so the only limiting factors are failure of nerve and worn, mis-matched Michelin and Pirelli tyres. The kick in the pants acceleration quickly becomes addictive and jumping from the Triumph to the Yam to the Lav provides proof that there really is no substitute for cubes. The 3CL has nearly a quarter litre on its British and Japanese contemporaries.

Unlike the smaller bikes with their 120 degree cranks, the Lav has a 180 degree unit placing the middle pot at the bottom of its stroke when the other two are at the top. This means eyeball bashing vibration as the needle rises past five grand on the Laverda badged Nippon Denso rev counter. But this is where the action is. No pain, no speed gain. Go on towards the 6500-7500rpm redline tacho zone and the pounding is relentless. Peak power of 81bhp comes in at 7200rpm. If you like your motorcycling physical the Lav's for you.

I'm attempting mobile mental arithmetic to translate my speeds into mph from the kph indicated on the green faced clock. But the 3CL keeps me far too occupied to practice mental dexterity. I later work out that 5000rpm in top gear gives around 90mph while a less fraught 4000rpm equates to about 70. First gear takes me comfortably past 40mph, flying all the way from 5000rpm. Urgent bellowing from the rubber mounted Lafranconi silencers rises to an explosive clamour as the revs are piled on. Not many sets of these original cans have survived. They're not Jota loud, but they certainly make the 3CL's presence felt.

Riding position is ergonomic perfection and goes a long way to make up for the other discomforts. My knees tuck neatly into detents at the rear of the wide fuel tank, and the Brevettato bars are infinitely adjustable to suit even the oddest shaped rider.

|

Something I would change -- and soon -- are the brake pads. The three Brembo discs fitted to the Lav usually provide excellent braking. But not on this bike. I'd dispensed with my usual practice of checking the brakes on an unfamiliar bike at low speed and am alarmed when a Give Way line approaches too quickly when I apply the brakes. Working down through the gears slows the beast enough to use what braking power there is and disaster is averted. A heavy, powerful bike like the 3CL needs all the brakes it can get.

Despite a fearsome reputation clutch action is reasonably light, needing only a gentle tug on the Tommaselli lever with its neat sculpted finger indents. But the clutch is slightly out of adjustment making it drag so neutral selection is virtually impossible at standstill.

Engineer Hugh Topping's bike is in good original condition, right down to the correct silencers and paintwork. The horns are the wrong type and are incorrectly mounted -- they should be under the headlamp -- and a previous owner has chopped the front mudguard.

When I swing the Lav onto its centrestand I'm taken aback by the easy action -- just as well because there's no prop stand fitted. Contrast that with the Trident's centrestand that operates like it was fitted as an afterthought. The weight distribution is all wrong for easy operation and the Trident leans at a worrying angle on the prop stand which has a reputation for snapping off.

Test bike 3CL has rare standard silencers, but horns are not

original and wrongly sited.

|

| Yamaha XS750s have a reputation for transmission

problems. Keep an eye on camchain wear and adjust regularly |

Richard Slater says that the robust motors rarely give trouble.

But as on any other 20 year old bike, electrics will be tired by now and Bosch ignition boxes, troublesome even when new, benefit from replacement with a modern computer controlled electronic ignition system. Once such is the box of tricks developed by Todd Laverda (0181 660 9917).

Availability of consumables and engine spares is good, but cycle parts and tinware are becoming thin on the ground.

The usually excellent Brembo triple discs fared so poorly on Classic Bike's test because of the brake pads. Original Brembo pads don't perform well and Slater recommends and supplies Ferodo replacements.

Gary Coull has owned 16 Laverda Jotas and many other Breganze triples: "I've done many miles on many bikes with few problems." But some aftermarket valves can fail says the former Lav breaker: "The heads fall off." Front cam chain tensioner blades sometimes snap if engine is built up wrong. Very early crankcases have one less bolt, identified by two webs on the crankcase at the back left of the barrel, later ones have three webs. Cast iron skulls can part company with cylinder heads. Standard oil filtration is poor so use quality oil and plumb in a full flow cartridge filter.

Coull recommends potential purchasers request rocker box covers be removed to check cams and warns that interchangability of engine parts means that Lav triples, especially exports, aren't always the model they claim to be.

Yamaha XS750s have few faults but cam chains are prone to stretch. On some early examples the seal between the gearbox and the 'middle' gearbox that drives the shaft let go allowing the oils to cross contaminate. The Hy-Vo primary drive chain can be noisy. The first examples have three sets of ignition points which are a pain to set up. Replace them with a maintenance free electronic ignition system.

Tyre manufacturers are making some excellent rubber suitable for classics. Transform the handling of your bike by binning period tyres. The Metzelers on our test XS are excellent and the new Avon Roadrunners on my own Trident make me wonder why I stuck with TT100s for so long.

Trident owners are spoilt for choice when it comes to specialist companies and improved components. For cost reasons Triumph fitted points ignition to triples right up to the end. Junk the points immediately and fit a Boyer Bransden or Lucas Rita electronic system. With the Boyer you'll need to fit 6V coils.

Duplex primary chains are now unobtainable. Norman Hyde (01926 497375) offers a dual single chain conversion. Otherwise it's a toothed belt drive and weight saving alloy pulleys.

Clutches can be prone to slip and are difficult to adjust. Poorly designed standard top hat clutch pull rods should be replaced with a tapered type either from Hyde or Performance Motorcycles (01568 750658). Performance also does some useful allen key mushroom tappet adjusters.

Wear prone original valve guides can be junked in favor of Colisbro ones and stainless and chromed valves are available.

The Yam and the Lav are the easiest to keep oil tight -- there are no pushrod tubes to seal -- and just look at the 3CLs chunky castings giving big gasket areas. Spares availability for all three bikes is good. If modifications are your thing forget about doing much to the Yamaha, but there's a huge network of specialists catering for owners of our other two test bikes.

If ever there was a nearly bike it's the XS750. Rated by owners in their day the XS has yet to earn a true classic cachet. But of the bikes on test it's the cheapest today, and is the value for the money choice to get a taste of triple ownership.

|

The XS750 also receives the Topping seal of approval: "Apart from being shaft drive, the Yam feels much like it was designed to the Japanese Trident, especially in terms of performance. The difference is that the XS needs more revs to deliver the goods." Switchgear comes in for particular praise. "These two bikes are perfect examples of Seventies Japanese and British philosophies."

|

"The bike never gets out of line but I did feel the back end squirm a couple of times." Mick expected the Trident to outperform his Yam, especially at the top end. "But acceleration wise I think the Trident and the Yam are much the same," says Mick. "It's such an easy bike to get on with."

Mick is wowed by the amount of poke that the Laverda's extra quarter litre gives. Dodgy brakes apart, the only thing to spoil Mick's riding enjoyment is the Lav's top heaviness.

And Mick's verdict. "I'll stick with my Yam for touring and take the 3CL for out and out sporty stuff. The Trident is a bit of both."

|

"It's a bit slow for a 750, possibly because of the tortuous route that the drive must take from the crank, through a middle driven gear and shaft drive to the rear wheel. That must sap a fair bit of power. But the advantage is no torque reaction effect and a silky gearchange," adds the Guzzi rider.

"The Laverda is brutal and wants to fall into tight corners. The Triumph has a superb grunty power delivery and feels like it could be slung about all day long, although you'd soon get bored of travelling round corners on the footrests. The Yam has a reputation for self destruct gearboxes, but wearing my bank manager's hat I'd vote for the XS because they are so cheap."